Please, use the citation for this document: Zamecnikova, M. (2019) ‘Afghan Chess’ Atlantica, 3(1), Available at: https://atlantic-forum.com/content/afghan-chess

Republished by Usanas Foundation, Available at: https://usanasfoundation.com/afghan-chess

Welcome to the Afghan Chessboard

The war in Afghanistan has been one of the longest contemporary wars, starting with the Soviet invasion in 1979. For more than 40 years, Afghanistan has been a headline for war, conflict, instability, and mass migration to neighbouring countries and around the world. Since 2001, there have been significant opportunities caused by NATO intervention in Afghanistan after the Allies decided to invoke Article 5 following the 9/11 attacks on the United States. These achievements included improving former Afghan governance, developing civil society, and promoting the participation of women in politics. These were also the reasons for the international community’s ongoing presence after Osama bin Laden’s death in 2011 until the withdrawal agreement negotiated by the Trump administration in February 2020.

The collapse of the Afghan government and the Taliban’s recapture of power on 15 August 2021 has posed countless question marks for the West’s communication with terrorist groups, gender equality, human rights, and many more issues regarding pluralism, tolerance, and freedom. The end to “America’s longest war” has been an increasing problem in the international sphere, and foreign governments have been trying to respond with different policy proposals, although with limited success, such as the Doha agreement negotiated between the United States and the Taliban in 2020.[i] The failure of the Doha deal was mainly due to the exclusion of the former Afghan government, which threatened its legitimacy.

The chessboard dynamic in Afghanistan is changing every day, and the future movements of chess pieces can only be predicted to a limited extent as the situation is rapidly evolving. This article is not titled ‘Afghan Chess’ because the Taliban does not play this game (in fact, the Taliban recognises it as a form of gambling[ii]) but because one movement of any actor can rapidly and inevitably change the dynamic of the war. This article introduces three levels of Afghan security policy and elaborates on the drawbacks of the present scenario based on the lessons learned from the Vietnam War.

Safe Chessboard

What went wrong during 20 years of the Alliance’s presence? The primary challenge has always been how to ensure a stable Afghan security policy in case of the withdrawal of foreign combat forces, which Western powers feared would result in the power expansion of the Taliban throughout the country. Three different levels influenced Afghanistan’s security policy prior to the Taliban’s takeover:

- U.S.-Taliban negotiations

- Regional peace-making

- Intra-Afghan dialogues

This policy framework for the peace-making process had encompassed three critical elements: the first of which, the ‘U.S. and Taliban’, taking place on the international level. In this case, the international community was the main actor in achieving Afghan prosperity by influencing changes in foreign policy. The second was mainly about neighbouring countries and their attitude towards the Taliban. The last was the ‘Intra-Afghan’ position, which was the most significant policy point and involved the former Afghan government and control over Afghan territory. In this analysis, the presence of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization was evident in the second and third levels because of its role in supporting the Afghan government since 2001 and working in close coordination with the international community and partners, such as the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) and the EU.

The situation in Afghanistan is complicated and has taken a considerable amount of time and resources. According to many experts,[iii], [iv] the war in Afghanistan had become a new Vietnam War, which has even exceeded the latter’s duration.[v] This paper thus elaborates on a peaceful foreign policy scenario that follows the outline of the conclusion of the Vietnam War. Implementing the following strategies, drawing on the lessons from Vietnam, could have prevented the current chaos that we see when examining the Afghan chessboard:

- Putting a ceasefire in place

- Withdrawal of U.S. military forces

- Continued support of the central regime by the United States

First, however, in the following sections this article will outline the context in recent years leading to the present scenario in Afghanistan.

Context Chessboard Analysis

Afghanistan is currently one of the poorest and most unstable countries globally and poses a potential security risk to its neighbours caused by a long history of conflict and uncertainty in the Taliban’s rule. The instability has a significant impact on the safety and development of the whole region, but it has also affected the foreign policy of the international community. From 2001 to 2021, the United States and its NATO allies had provided considerable support for the recovery of Afghanistan. However, this recovery has fallen short of providing peace for the Afghan people.

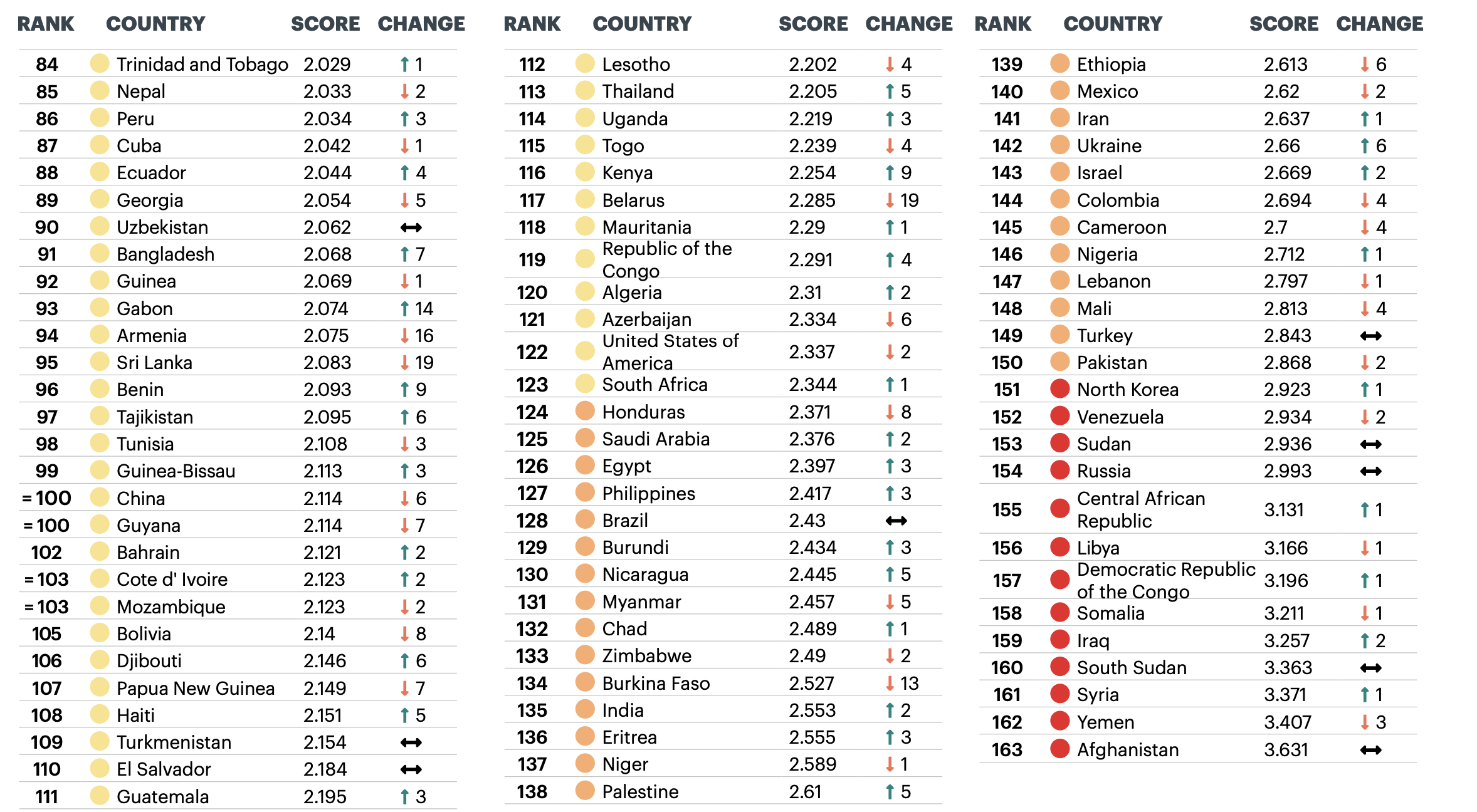

The situation is highlighted in Figure 1 below. Afghanistan achieved the rank of the least peaceful country (3.631) out of 163 independent states in the Global Peace Index 2021.[vi] According to the GPI, Afghanistan has been among the last three nations since 2010. In addition, over 52% of Afghan people reported suffering from violent crimes earlier this year, and 79% felt more threatened than in 2014. The figure also shows that there is no change in the peace index from the previous year. This stagnation is caused by the Taliban’s control of more territory than at any time since 2001, as well as the high number of deaths.

Figure 1: A Snapshot of the Global State of Peace

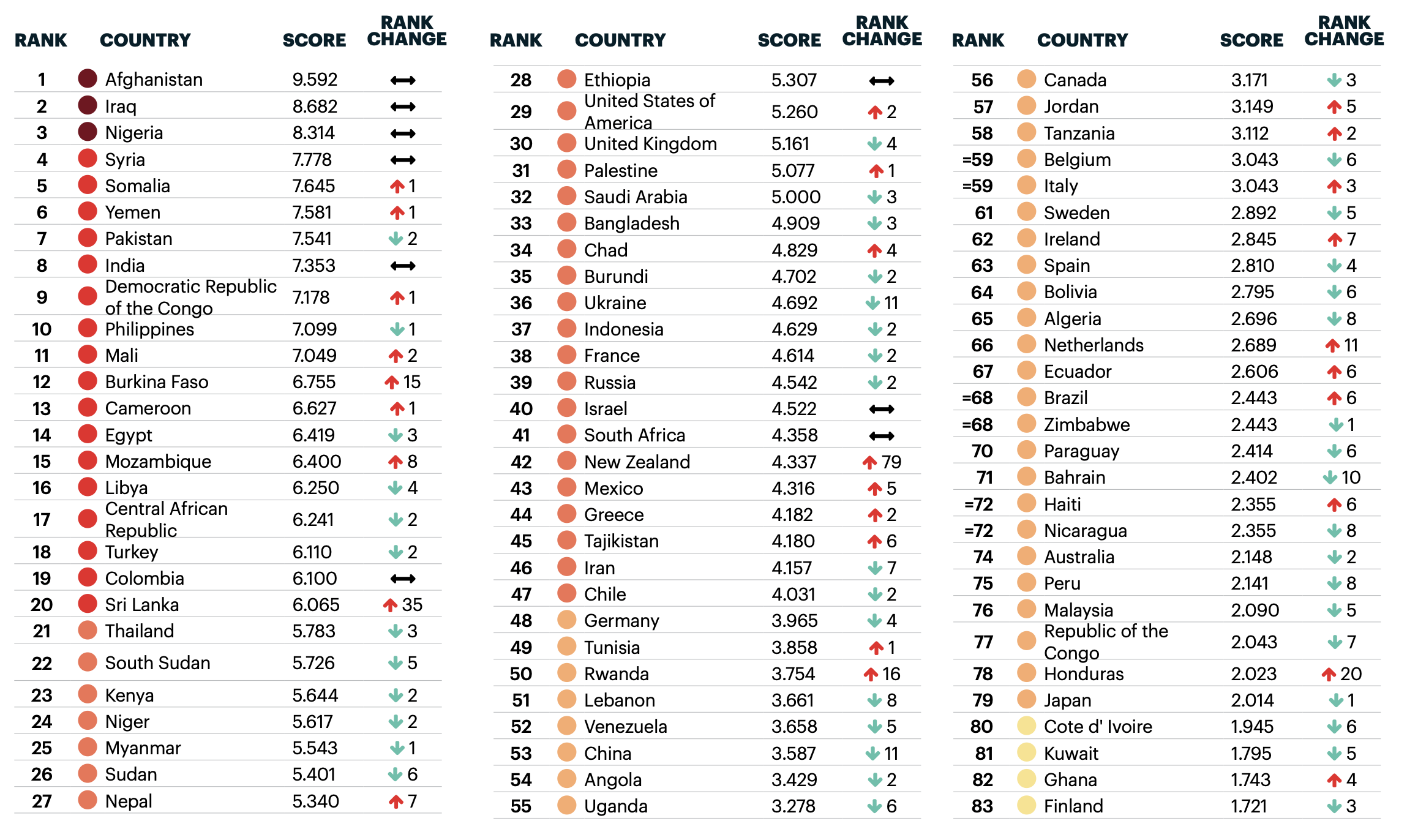

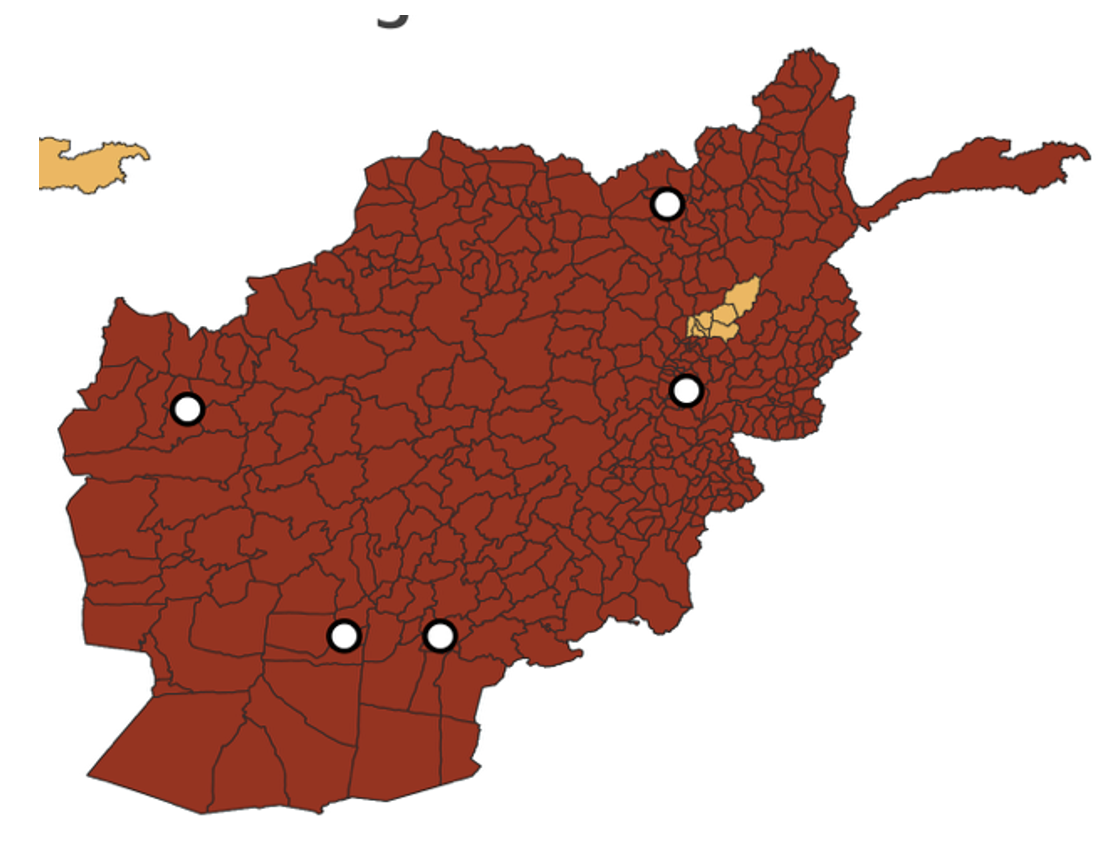

Another aspect to consider is terrorism because “terrorism is closely linked to political instability, sharp divides within the population, country size and further demographic, institutional and international factors.”[vii] Figure 2 shows that Afghanistan is one of the most affected countries by terrorism, alongside Syria, Iraq, and Nigeria. These four countries are labelled as epicentres. According to the UNAMA,[viii] the Taliban caused 47% more battle-related deaths in the first half of 2021 than over the same period last year. Moreover, the Taliban rapidly expanded its direct territorial control. In August 2021, we witnessed the Taliban’s rapid recapture of Afghanistan, from controlling around 10% of the country’s territory to almost the whole country, including the country’s capital, Kabul. The Global Terrorism Index[ix] provides crucial evidence of the increasing violence and expansion within the country’s territory even before the Taliban’s near-total takeover, which was accelerated by the signature of the Doha peace agreement. The international community is currently observing how the Taliban will interact with militant groups, such as Al-Qaeda and Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), because the evolution of these interactions can predict the future movement of the chess pieces.

Figure 2: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism

Both figures above show that the circumstances for lasting peace were not appropriate. Angstrom claims that “[…] in the Afghan case, estimates show that nearly 50% of the indigenous population has become casualties – killed, wounded, or homeless – over the past three decades of war.”[x] Therefore, changes in foreign policy and the maintenance of external forces have been needed to overcome these issues and establish order in the territory. Although the United States was seen as the primary contributor of troops, there has been a significant decline in U.S. combat forces in Afghanistan since 2011, caused by increasing resistance to a long-term war with an uncertain outcome.[xi]

The Afghan war and many previous conflicts have destroyed the beautiful country that is today one of the poorest in the world and prone to radical regimes. Short-term goals, such as the dismantling of Al-Qaeda, quickly replaced long-term strategy, including nation-building. However, the intention to rebuild Afghanistan rapidly came to a stalemate, because the international community tried to make political reforms by promoting democracy, which even deepened political instability. The security issues in Afghanistan have deepened over time and now are mainly caused by the expansion of the Taliban throughout the country’s territory with the simultaneous withdrawal of U.S. combat forces.

Retreat vs. Checkmate

After eighteen years of unsuccessful warfare, peace talks between the Taliban and the United States began in 2019, “but the framework glosses over many of the thorniest issues and, despite the desire for peace, there are concerns about motivations on both sides”.[xii] This section critically investigates the apparent purpose of the American as well as NATO’s withdrawal and the reasons for the Taliban’s violence.

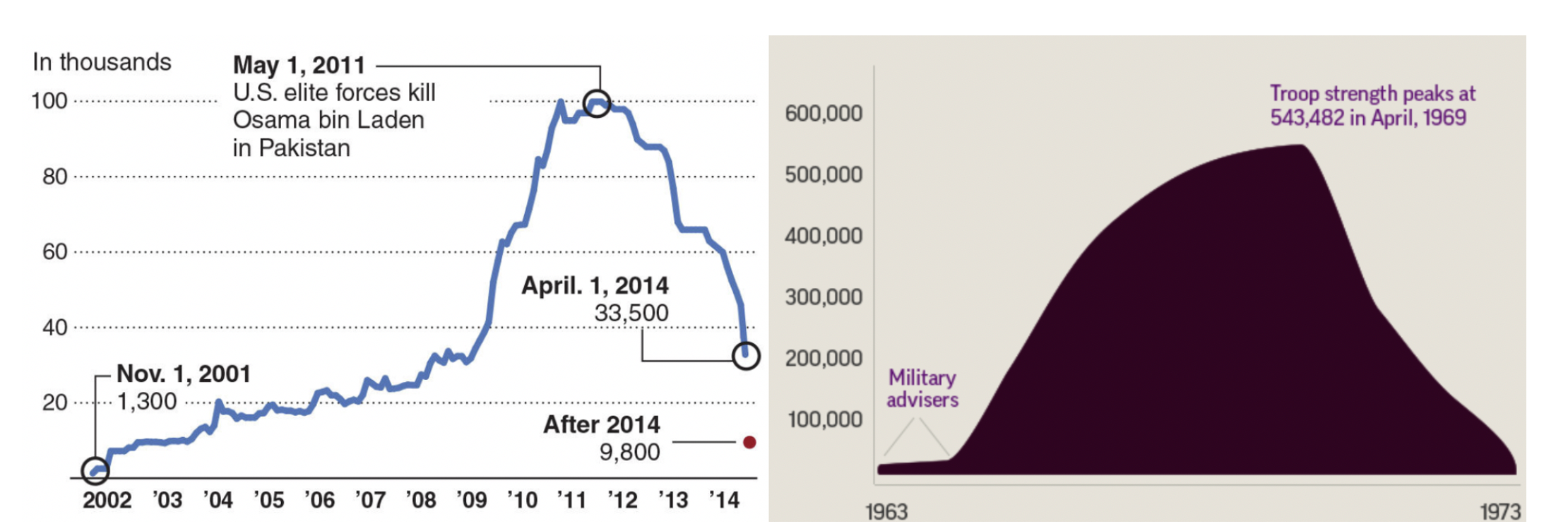

Figure 8 (see end of article) illustrates a significant decrease of American combat forces in Afghanistan. Therefore, one would argue that if the combat forces of the international community are not needed anymore, Afghan citizens should feel considerably safer in their home country. According to the Asia Foundation’s public opinion survey, Figure 3 shows what percentage of Afghan respondents answered that they “always,” “often,” or “sometimes” fear for their own personal safety or for that of their family. Interestingly, this number has increased since 2006, and this high level has remained stable in recent years, 70.7% in 2017 and 71.1% in 2018, respectively. After the assassination of Osama bin Laden in 2011, which is also presented in Figure 3, fear for personal and family safety decreased by 6 percent, but the reduced proportion more than doubled in the following years with the rapid decrease of the international community’s presence.

Figure 3: Fear for Personal and Family Safety – Percent who respond “always, “often,” or “sometimes”

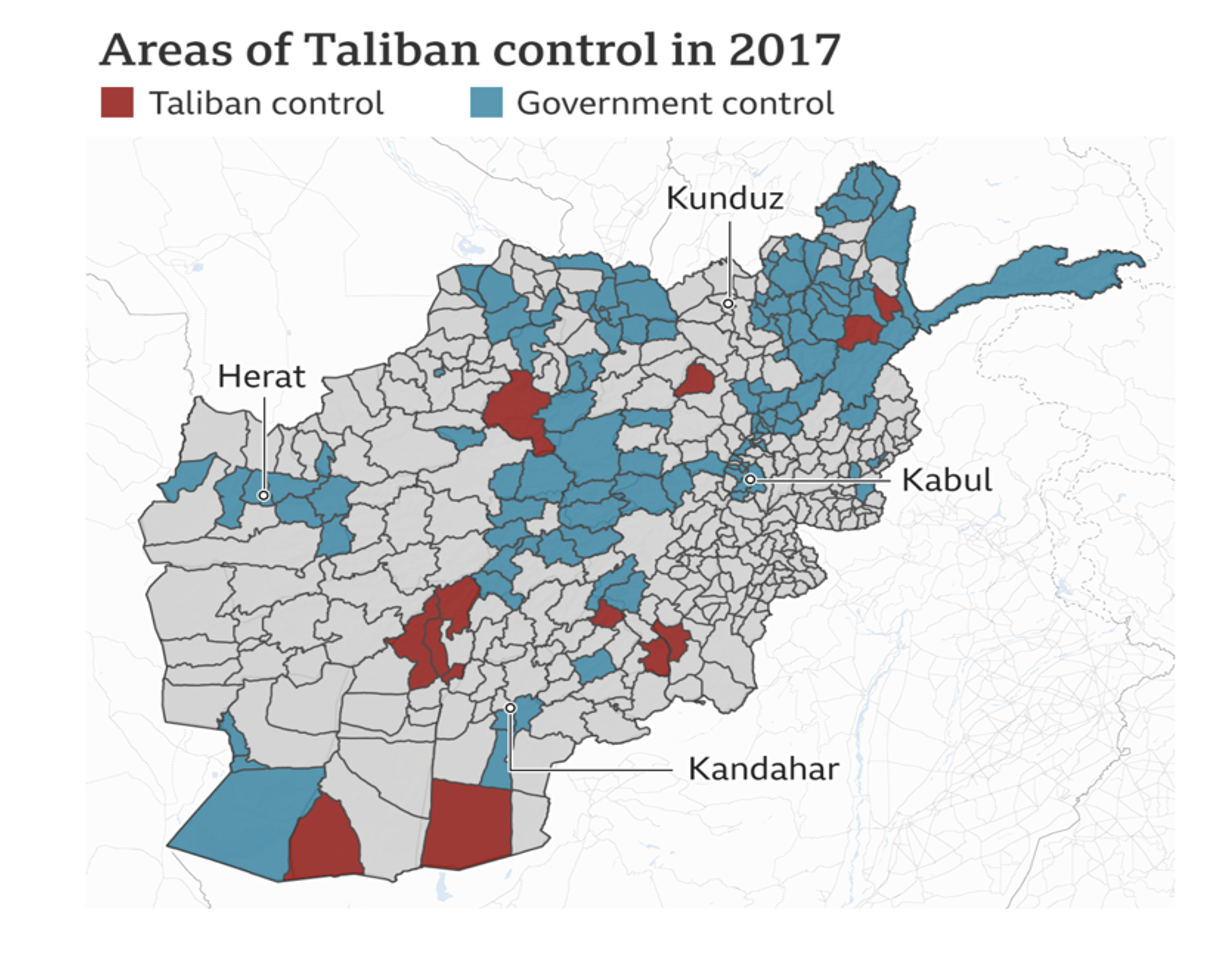

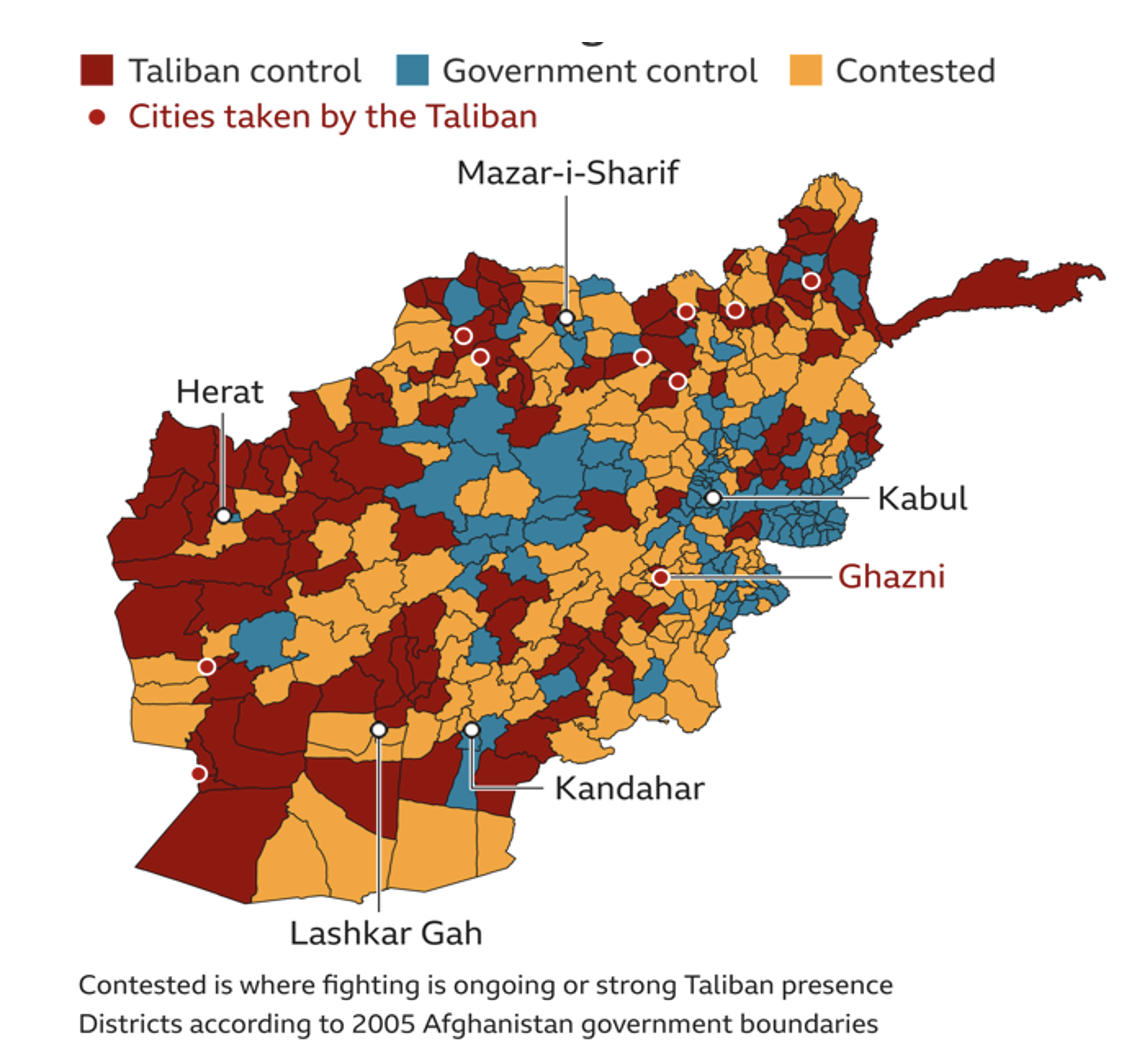

Contrary to U.S. plans, many politicians and military commanders, such as the former U.S. President George Bush or former head of UK Joint Forces Command Gen Sir Richard Barrons, argued that the withdrawal of troops was a huge mistake.[xiv], [xv] The vital component is that the Taliban was capturing more cities alongside the withdrawal. Even though Figure 5 shows relatively little Taliban control compared to Figures 5 and 6, almost half of the Afghan population reported living in areas controlled by the Taliban in 2017.[xvi] Figure 5 represents the Taliban’s more extensive control than in 2001. After the withdrawal of the international community, there is a high risk of increasing terrorist entities caused by instability in Afghanistan, which will also pose a significant threat to Europe and other parts of the world in the near future.

The considerable decrease of foreign troops (Figure 8), the larger fear within the country (Figure 3), and the higher perception of the need for external support resulted in the continuous advancement of the Taliban (Figure 4, 5, and 6).

Figure 4: Taliban’s control in 2017

Figure 5: Taliban’s control on 11 August 2021

Source: BBC, 2021b

Figure 6: Taliban’s control on 16 August 2021

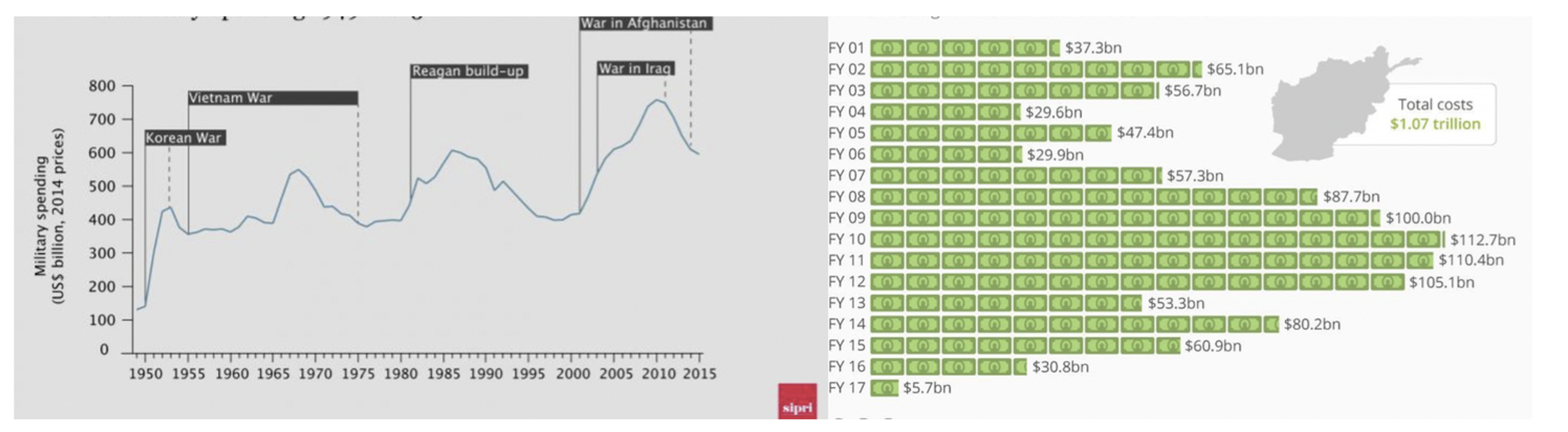

Although Figures 2 and 3 show that the decline of foreign support bothered Afghan citizens, the United States insisted on its current withdrawal policy with the final date of 31 August 2021. One may argue that the purpose of American withdrawal was the ongoing peace process. However, the Pentagon said that “the Afghan war is costing American taxpayers, and with no end in sight they may have to keep footing that bill for years to come,” which seems that the reason for withdrawal is related to an economic issue.[xvii] Clear evidence of American spending is provided in Figure 7, which shows that the Afghan war, alongside the Iraq war, has come to be America’s trillion-dollar conflict and the most costly failed war since 1949.

Figure 7: U.S. Military Spending, 1949 – 2015, and detailed costs, 2001–2017

Even though now everybody is talking about the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, NATO also has had its reasons for the drawdown of its Resolute Support Mission since 1 May 2021[xx]—namely that the Resolute Support Mission would be impossible to maintain without American support. Moreover, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg argued that it is time for Afghan citizens to achieve sustainable peace in their country by themselves. However, the Special Inspector for Afghanistan Reconstruction concluded that the situation in Afghanistan was “consistent with a largely lawless, weak, and dysfunctional government”.[xxi] Therefore, it could have been predicted that the Afghan army would quickly disintegrate after NATO’s withdrawal because there was neither a strong sense of national duty among the Afghan army nor ideological cohesion among its leaders.[xxii]

Championship Blunders

America’s main issue during the Afghan war was that “we ended up staying in Afghanistan for another five years, another eight years, another ten years. And we would do it not with clear intentions but rather just out of inertia,” said former U.S. President Barack Obama during an interview about the nature of the war.[xxiii] A similar situation was seen in the never-ending Vietnam War, where the United States fought against the political organisation called the Viet Cong. The Vietnam War ended after a simple foreign policy framework was implemented, which could have been applied to the Afghan war, as well.

After the battle, looking at the situation retrospectively, there are many ways to analyze how the withdrawal from Afghanistan could be improved. The following lessons from the withdrawal at the end of the Vietnam War have been available and could have been used as a lesson learned since the beginning of the Afghan war.

1. Putting a ceasefire in place

Almost two years before the end of the Vietnam War, Henry Kissinger, the National Security Advisor, arrived in Washington from Paris with a peace proposal that recommended a ceasefire in Vietnam.[xxiv] The document, called the Paris Peace Accords, was signed by North and South Vietnam as well as the United States, and American forces began to withdraw from Vietnam. The lessons drawn from the Paris Peace Accords reflect the need to have a ‘functioning’ peace agreement and ceasefire in place among all actors before beginning to withdraw troops.

In July 2018, there were three days of ceasefire, and Ashraf Ghani, former Afghan president, said that “he is willing to negotiate with the Taliban at any time and in any place.”[xxv] However, peace negotiations did not occur because the Taliban refused to talk with the “slave” and “puppet” regime in Kabul. The Taliban was willing to have direct peace talks exclusively with the United States regarding the withdrawal of foreign combat forces as part of the deal. Thus, there were several peace talks between the United States and the Taliban, where both sides agreed on a framework for complete U.S. withdrawal in exchange for Taliban counterterrorism guarantees.[xxvi] The question then was how could these peace talks remain in force with the former dysfunctional Afghan government in power. This turned into a vicious cycle as America was worried about economic policy (Figure 7), the Taliban was seeking power gains within Afghanistan (Figure 4, 5, 6), and the former Afghan military did not fight for its citizens.

A better scenario would have been to include the former Afghan government and set up a peace proposal with all three actors at one table or, even better, negotiate the peace agreement on the intra-Afghan level, because every party knew that America could not be present forever.

However, the former Afghan president never had strong enough leadership to participate in peace talks between the United States and the Taliban. According to General Joseph Votel, head of the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), “it is my observation, from my close discussions with U.S. special envoy [Zalmay Khalilzad] that he is in fact consulting with [former] President Ghani on a regular basis, keeping him well informed and that the actual initiation of these discussions was done with President Ghani’s knowledge and support.”[xxvii] On 29 February 2020, the Doha agreement was signed between the Taliban and the United States, excluding the Afghan government. This comprehensive peace agreement was an attempt to call on intra-Afghan dialogue and negotiations, which ended only in prisoner exchanges, including those accused of serious crimes.[xxviii] Furthermore, more than 4,500 attacks were reported by the Taliban after the agreement until 15 April 2020.[xxix]

2. Withdrawal of U.S. military forces

U.S. President Richard Nixon and Kissinger were afraid of a complete U.S. withdrawal because it was a significant step that could not be implemented without completing previous stages.[xxx] In other words, they needed to be sure that the withdrawal would be safe for Vietnam. Moreover, the Viet Cong had similar demands in Vietnam as the Taliban has in Afghanistan—unconditional withdrawal of all U.S. forces from Vietnam and the establishment of a government without the former president of South Vietnam. Therefore, they conducted as many possible peace talks as needed before the U.S. withdrawal. At the end of the war, Nixon announced a phased withdrawal of about 150,000 troops within one year.[xxxi] The lesson to be drawn is the fact that the U.S. military forces left Vietnam when there was an obvious end to the war and an established government.

Figure 8: Comparison of U.S. Troops in the Afghan war and the Vietnam War

Figure 8 illustrates a rapid decrease of U.S. forces in the ongoing Afghan war and the withdrawal of external forces in the Vietnam War. Although there were almost six times more U.S. troops at the peak of the Vietnam War than in the Afghan war, the Vietnam War also had clear allies, and the United States was supported by a more significant proportion of international combat forces than it was in the Afghan war.

At present, all foreign forces have been withdrawn from Afghanistan without a ‘working’ peace proposal. Before August 2021, the Taliban was primed to take over Afghanistan more so than at any point since 2001, and this strength was growing with the decreasing presence of foreign combat forces. International troops should have stayed until the negotiation of a ‘functioning’ peace proposal between the Taliban and the United States, and an intra-Afghan dialogue was in place.

Another factor to be considered as a failure in this stage is the time management of withdrawal. The date was changed many times during 2021, from 1 March through 11 September and 31 August, which also caused significant pressure and chaos.[xxxiv]

Now, the United States should not only negotiate with the Taliban but also focus on other independent insurgent elements throughout the country, such as ISKP, which recently launched a terrorist attack at Kabul’s airport and killed over 180 people, including 13 U.S. service members.[xxxv]

3. Continued support of the central regime by the United States

Establishing bilateral relations should be the final step after the peace agreement, ceasefire, and withdrawal of American combat forces. Vietnam received reconstruction aid immediately after the American withdrawal, which was promised by Nixon with long-term support.[xxxvi] On the one hand, Article 21 of the Paris agreement on Vietnam (Paris Peace Accords) states that the United States had an obligation “to contribute to healing the wounds of war and to post-war reconstruction in Vietnam […] without setting any political conditions.”[xxxvii] On the other hand, the United States wanted the Democratic Republic of Vietnam to normalise internal relations between the two countries in the exchange—similar to the intra-Afghan talks. The aid that was provided by the United States was a crucial part of maintaining bilateral relations between the North and the South. Although the United States ended foreign aid after North Vietnam took over South Vietnam, the U.S. aid program in Vietnam expanded gradually in the 1990s.

The United States should support Afghanistan after the peace talks, negotiation, and withdrawal of forces. This phase is crucial because the stronger the ties are among all participating actors, the more a sustainable peace is possible after the conflict. Then, Afghanistan can focus on the secondary challenges to rebuild the country’s economy, combat corruption, and reduce poverty, and America as well as Allies can continue to help, organise, train, equip, and sustain Afghan troops that will establish law and order alongside the future legitimate Afghan government.

Domination

The reason for NATO to go to Afghanistan after invoking Article 5 was to confront Al-Qaeda and those who attacked the United States on 11 September 2001. This mission was partly concluded when Osama bin Laden was killed in May 2011. Symbolically, the Biden administration set up a new deadline for troop withdrawal in September 2021, which was then changed to the end of August, two weeks before the deadline. As argued in this paper, the current situation for the withdrawal of American forces is the exhaustion of patience with the long war in Afghanistan rather than the courage of either the Biden or Trump administrations.

There was always a place to show the Afghan people how to build a military structure, but there is no capacity to change the mentality towards the definition of the state. After 20 years of fighting, the United States has put down its weapons without having a ‘functioning’ peace proposal with the Taliban. Although President Biden was calling on Afghan leaders to fight together against the Taliban before its recapture, “Afghanistan, the endless war” is still considered America’s trillion-dollar conflict and most costly failed war since 1949 (see Figure 7).[xxxviii]

The chess moves are uncertain in the near future, especially after the recent terrorist attack by the ISKP at the Hamid Karzai Airport. However, one thing is clear: the withdraw will have negative consequences, and future armed attacks on Allied countries are highly likely to occur, resulting in increased expenses on counter-terrorism policies and another invocation of Article 5. The moves of the pieces in the Vietnam War could have been used on the Afghan chessboard not only to help implement the peace agreement but also to ensure a smoother withdrawal from Afghanistan and overall endgame.

Bibliography

[i] “Timeline of U.S. Withdrawal from Afghanistan,” FactCheck, August 2021, accessed 30 August 2021, https://www.factcheck.org/2021/08/timeline-of-u-s-withdrawal-from-afghan….

[ii] “Chess May Be Banned in Afghanistan,” WorldChess, 2021, accessed 30 August 2021, https://worldchess.com/news/all/chess-may-be-banned-in-afghanistan/.

[iii] A. Gawthrope, “Afghanistan and the Real Vietnam Analogy,” The Diplomat, August 2021, accessed 5 September 20201, https://thediplomat.com/2021/08/afghanistan-and-the-real-vietnam-analogy/.

[iv]C. Risen, “Afghanistan, Vietnam and the Limits of American Power,” The New York Times, 17 August 2021, accessed 5 September 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/17/us/politics/vietnam-war-afghanistan.html.

[v] R. Buzzanco, “What can Vietnam War teach us about Afghanistan, North Korea?” Houston Chronicle, 2017, accessed 2 March 2019, https://www.houstonchronicle.com/opinion/outlook/article/What-can-Vietna….

[vi] Global Peace Index, “Vision of humanity,” June 2021, accessed 2 August 2021, https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/GPI-2021-web….

[vii] T. Krieger and D. Meierrieks, “What causes terrorism?” Public Choice 147, no. 1 (2011): 3–27.

[viii] UNAMA, “2021 Civilian Casualties Set To Hit Unprecedented Highs In 2021 Unless Urgent Action To Stem Violence,” UN Report, accessed 29 August 2021, https://unama.unmissions.org/civilian-casualties-set-hit-unprecedented-h…–-un-report.

[ix] Global Terrorism Index, “Vision of humanity,” 2020, accessed 2 August 2021, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/GTI-2020-web-2….

[x] J. Angstrom, “Inviting the Leviathan: External forces, war, and state-building in Afghanistan,” Small Wars & Insurgencies 19, no. 3 (2008): 374–396.

[xi] “Afghanistan war: Trump’s allies and troop numbers,” BBC News, 2017, accessed 2 March 2019, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-41014263.

[xii] “America and the Taliban are edging towards a deal,” The Economist, 31 January 2019, accessed 3 March 2019, https://www.economist.com/asia/2019/01/31/america-and-the-taliban-are-ed….

[xiii] “Afghanistan in 2018: A Survey of the Afghan People,” The Asia Foundation, 2018, accessed 30 August 2021, https://asiafoundation.org/publication/afghanistan-in-2018-a-survey-of-t….

[xiv] Joseph Lee, “Afghanistan troop withdrawal a strategic mistake, warns ex-general,” BBC News, 8 August 2021, accessed 12 August 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-58139590.

[xv] “The Daily 202: George W. Bush is right about Afghanistan. It doesn’t matter,” The Washington Post, 16 July 2021, accessed 8 August 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/07/16/daily-202-george-w-bu….

[xvi] “Mapping the advance of the Taliban in Afghanistan,” BBC News, accessed 16 August 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-57933979.

[xvii] PBS News Hour, “Pentagon says war in Afghanistan costs taxpayers $45 billion per year,” PBS, 2018, accessed 8 March 2019, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/pentagon-says-afghan-war-costs-tax….

[xviii] “The Financial Cost Of U.S. Involvement In Afghanistan,” Forbes, 24 August 2017, accessed 8 March 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2017/08/24/the-financial-cost….

[xix] “Launches extended military expenditure data covering 1949–2015,” Stockholm International Peace Institute, 2016, accessed 8 March 2019, https://www.sipri.org/news/2016/sipri-launches-extended-military-expendi….

[xx]“NATO Allies decide to start withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan,” NATO, accessed 5 September 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_183086.htm.

[xxi] “Afghanistan has a ‘largely lawless, weak, and dysfunctional government,’ watchdog says,” Washington Examiner, accessed 8 March 2019, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/policy/defense-national-security/afgh….

[xxii] “Why did the Afghan army disintegrate so quickly?” Al Jazeera, accessed 5 September 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/8/17/why-did-the-afghan-army-disintegrate-so-quickly.

[xxiii] B. Woodward and B. Gaines, Obama’s Wars (New York: Simon & Schuster Audio, 2010), 374.

[xxiv] T. Szulc, “How Kissinger Did It: Behind the Vietnam Cease-Fire Agreement,” Foreign Policy 15 (1974): 21–69, doi:10.2307/1147928.

[xxv] “A Vietnam “Solution” to the Afghanistan War?” The National Interest, 2018, accessed 9 March 2019, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/vietnam-“solution”-afghanistan-war-24737.

[xxvi] “Pakistan to Host Next Round of US-Taliban Peace Talks,” VOA, accessed 9 March 2019, https://www.voanews.com/a/taliban-announce-surprise-talks-with-us-in-pak….

[xxvii] “Afghan president supported start of U.S.-Taliban talks: U.S. general,” Reuters, accessed 30 August 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/usa-afghanistan-ghani-idINKCN1QO25W.

[xxviii] “Taliban Prisoners Release: Afghan Government Begins Setting Free Last 400,” BBC, accessed 30 August 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-53775035.

[xxix] “Taliban step up attacks on Afghan forces since signing U.S. deal: data,” Reuters, accessed 30 August 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-afghanistan-taliba….

[xxx] S. Walker, “The Interface between Beliefs and Behavior: Henry Kissinger’s Operational Code and the Vietnam War,” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 21, no. 1 (1977): 129–168.

[xxxi] G. Herring, America’s Longest War –the United States and Vietnam, 1950-1975 (McGraw-Hill, Boston – fourth edition, 2002), 288.

[xxxii] US Department of Defense, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy, 2018, accessed 30 August 2021, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf.

[xxxiii] Ap Explore, “Vietnam: The Real War,” AP, 2013, accessed 3 March 2019, https://www.ap.org/explore/vietnam-the-real-war/.

[xxxiv] “Timeline of U.S. Withdrawal,” FactCheck.

[xxxv] “US forces strike against ISKP suicide bombers in Kabul, officials say,” The Guardian, 29 August 2021, accessed 30 August 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/29/afghanistan-fresh-blast-ne….

[xxxvi] T. Lang, “Economic Debates in Vietnam: Issues and Problems in Reconstruction and Development,” Singapore, 1985, pg. 16.

[xxxvii] C. Menétrey-Monchau, American-Vietnamese relations in the wake of war (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co, 2006), 249.

[xxxviii] “The departure of American troops risks civil war, and many Afghans fear the return of a fundamentalist society,” The Guardian, 8 February 2019, accessed 6 August 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/feb/08/us-afghanistan-civ… fundamentalist.

[xxxviv] The Times of Israel: https://www.timesofisrael.com/at-least-26-killed-as-is-suicide-bomber-targets-kabul-shrine/

[xxxvv]World Politics Review: https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/trend-lines/29925/the-u-s-failure-in-afghanistan-burundi-s-charm-offensive-and-more

[xxxvvii] CNBC https://www.cnbc.com/2021/09/09/ashraf-ghani-afghanistan-ex-president-issues-explanation-after-fleeing.html

Image: Author’s own elaboration